Territorial synagogues

Owing to numerous trade routes, Wroclaw has become a place of exchange not only for material goods but also for information from various regions of Europe. Traders from different cultures and nationalities met here – temporarily, but regularly. Even before the emancipation edict, Jews could come to Wroclaw for several fairs a year, so, paradoxically, they were present and visible in the city despite the lack of permanent residence. Trade and cultural exchange accelerated over time, which was demonstrated by the growing number of houses of worship. But what is the relationship between trade and synagogues?

European Jews were not a homogeneous group – they differed in the language, customs, rituals and traditions, including religious ones, prevailing in a given country. That is why territorial synagogues, i.e. houses of worship, for Jews from a specific city or region were established in Wroclaw. As a rule, these were small rooms in tenement houses around the then Jewish Square. Jews from Lithuania, Volhynia, Białystok and Głogów had their separate synagogues, which mostly functioned until the beginning of the 20th century. Among the oldest territorial synagogues, we should mention the Wołyńsko-Krotoszyńska Synagogue, which was established in the 17th century and was located at the present Kazimierza Wielkiego Street. On the other hand, the buildings of the commune also housed the shtiebel, i.e. the house of worship of Polish Hasidim.

There were also smaller, private houses of worship, especially among the wealthy and influential townspeople. They served mainly the owner’s family – there were several such private synagogues on the present Św. Antoniego Street. Each of the larger social institutions, such as a hospital or an orphanage, had its own synagogues for the dependents and staff of the institution and often also the residents of the neighbourhood to use them.

The Jewish community was not only the organizer of the religious life of Wroclaw Jews, but also performed numerous social, cultural, educational, organizational and informational functions. The management office was initially located at Krupnicza 11, but later, in 1906, it was moved to a new building at today’s Włodkowica 5-9, where offices belonging to the commune are still located.

The National Synagogue

The Silesian Jews, on the other hand, could use the National Synagogue, which was located in the courtyard of the Pokoyhof passage and operated from the 18th century. The rabbi’s office was located on the ground floor of the building, and about three hundred people could use the synagogue during the prayers. Until the White Stork Synagogue was built, the National Synagogue served as the main prayer house in Wroclaw. The building from the 17th century, despite being renovated, fell into disrepair, so it was demolished, and the synagogue was first moved to the present Włodkowica Street, and then to the present Muzealny Square, where it was devastated during Kristallnacht.

The White Stork Synagogue

The expanding Jewish community needed a prayer house that would meet its requirements. The initiative to build a new synagogue came from an association of liberal Jews, who soon began collecting the necessary funds. Although the Prussian authorities had previously pressured the community to provide a synagogue accessible to everyone, this demand was not fulfilled for many decades due to the emerging conflicts between liberal and conservative members of the community. Tensions between the two fractions were resolved after the division into two separate groups led by two independent rabbis – one was a group of conservative Jews and the other – liberal. From that moment on, there was a relative order in the Wroclaw commune.

When the decision to build a synagogue was taken, its design in the Classicist style was prepared by Carl Ferdinand Langhans, an outstanding German architect, who also designed the building of the Wroclaw Opera a decade later. Officially, the White Stork Synagogue was opened in 1829, but for the first years, it was the private house of worship of the Society of Brothers, which initiated its construction. In 1847 it became the main synagogue of the liberal part of Wroclaw Jews. Its first rabbi was the outstanding Abraham Geiger, who led it in the spirit of reform. Its interior also reflected a bold, though symbolic, departure from a conservative understanding of Jewish practices, for example, by reading the Torah from the place where the Aron Kodesh stands, i.e. at the eastern wall of the synagogue. Another innovation was that men and women used the same entrance to the building, and sermons were given in German. However, it did not last long because the White Stork Synagogue was given back to conservative Jews who returned to the traditional order. The New Synagogue, on the other hand, became the house of worship for liberal Jews. This change was caused by the expansion of the liberal community, for which the synagogue in today’s Włodkowica Street was insufficient, so it was necessary to build another house of worship.

The White Stork Synagogue, under the care of a conservative community, gained a classic look: during the renovation, a bimah for reading the Torah was placed in its centre, and separate staircases for women and men were built. The women prayed separately on the balcony of the synagogue. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the religious infrastructure was expanded: a mikveh was built, i.e. a ritual bathhouse for both women and men, and a shul, i.e. little synagogue. To this day, shul is located at the White Stork Synagogue, and it is the only place where prayers have been held continuously since its inauguration – the only exception was the period of World War II.

Ten years before the outbreak of the war, the synagogue was renovated. During Kristallnacht, the interior of the synagogue was looted and destroyed. However, owing to the close-up development and numerous buildings surrounding it, the Nazi militias refrained from aggressive devastation because arson could also damage the nearby tenement houses. The house of worship functioned until 1941 when the Nazis closed it and then allocated it as a warehouse to store the property of Jews who had been deported. The synagogue, however, survived and – even though the post-war times were also not favourable to it – it remains a showcase of the Wroclaw Jewish community to this day.

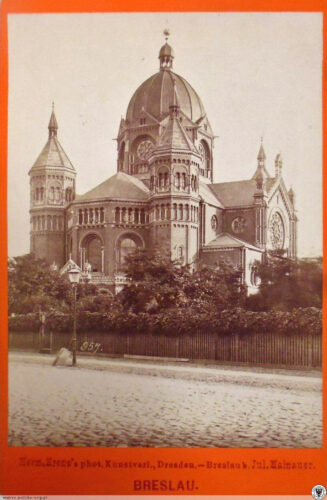

The New Synagogue

The New Synagogue, which before its demolition was located at today’s Łąkowa Street, was built for liberal Jews in 1872. It was an extremely majestic building in the Romanesque-Byzantine style, designed by Edwin Oppler. Only the Berlin synagogue was larger across Germany; the momentum and wealth undeniably testified to the success of the Wroclaw community. There could be eighteen hundred people inside, so it was also a meeting place for Jews from outside Wroclaw. Moreover, the New Synagogue was surrounded by a green belt, and next to it there was a building of the Jewish community.

The opening ceremony of the New Synagogue was a large and symbolic step that indicated changes in the community. During the opening ceremony Manuel Joël, the Liberal Rabbi, was accompanied by Gedalje Tiktin, the Conservative Rabbi. The presence of both rabbis indicated a reconciliation in the Jewish community, where tensions often arose between the former rabbi Abraham Geiger, a reformer and visionary, and the conservative rabbi.

In the mid-1930s, the synagogue was renovated, and the design of the interior was entrusted to a well-known painter from Wroclaw, Heinrich Tischler. However, a few years later, during Kristallnacht, the Nazis set themselves the goal of completely destroying the largest Jewish house of worship in Wroclaw. First, they set fire to the synagogue, and then, in order to destroy it even faster and more efficiently, they blew it up while the remains were dismantled. Today in its place, there is only the Memorial to the Victims of the Kristallnacht, on which the words of Psalm 74 are quoted: They burned your / sanctuary to the ground / they defiled the dwelling place / of your Name.

Fränkel Foundation Jewish Theological Seminary

One of the greatest institutions was the Jewish Theological Seminary, which was established in 1854 and quickly became the centre of religious life. The foundation established by Joseph Jonas Fränkel supported many centres for the people in need but also focused on the creation of an innovative university to educate future German rabbis. In his will, Fränkel expressed his willingness to create it, and he also allocated funds for this purpose. The school was run by Zacharias Frankel, while the initiator of its creation was Rabbi Abraham Geiger. Later, however, he was not allowed to decide about the education in the seminary because he was trying to push through reform ideas. Unfortunately, his plan for a radical revival of Judaism was not accepted by the conservative community, which made up the majority of the lecturers.

The Wroclaw seminar was the first of its kind in Central Europe and later became famous as one of the most important in the world. Its aim was to modernize the education of rabbis so that their comprehensive education in the field of Jewish theology would also keep pace with the secular world. Graduates of the university were not only to become teachers and rabbis but to also professionally serve their future community. The lecturers were outstanding rabbis and scholars, including Jacob Caro, Manuel Joël or Heinrich Graetz. The course for rabbis lasted seven years, but it was also possible to pursue three-year studies to educate future seminary teachers. Over time, the program offers also began to include evening courses for both adults and youth groups.

The Jewish Theological Seminary was located at today’s Włodkowica Street. Due to renovation, the magnificent tenement house was adapted to educational needs: there were lecture halls and a small internal synagogue. The university published its own monthly magazine, which quickly became a widely read and opinion-forming medium for the Jewish community. The seminar could also boast important collections of cultural goods; it had, for instance, a well-stocked library, as well as an impressive collection of Silesian Judaica on display at the Jewish Museum. The book collection also included the valuable collection of Leon Saraval, consisting of manuscripts and prints created in Jewish languages – Hebrew, Yiddish, and Ladino. The works came from Europe and the Middle East, some of them dated back to the 13th century. In 1938, the collection was confiscated by the Nazis, and only a dozen years ago, a small part of it was regained, as a result of which it came back into the possession of the Jewish community in Wroclaw and was deposited by it at the University Library in Wroclaw.

Owing to a thriving seminary, Wroclaw became one of the most important centres for teaching Jewish thought. Later, the European institutions took the Wroclaw school as an example. Unfortunately, the seminary shared the fate of all Jewish institutions in Wroclaw – the university was devastated by Nazi militias during Kristallnacht and that same year, it was formally closed, although the last rabbinical semikhah was conspiratorially awarded at the beginning of 1939.